By Kathy Jones

More than three quarters of the 99 journalists and media workers killed worldwide in 2023 died in the Israel-Gaza war, the majority of them Palestinians killed in Israeli attacks on Gaza. The conflict claimed the lives of more journalists in three months than have ever been killed in a single country over an entire year.

Investigating the circumstances of these war-related deaths – which also included three Lebanese and two Israeli journalists – was particularly challenging, not only because of the large number of deaths in a short time, but also because of the loss of those who could have provided more information. Many journalist victims’ families were killed along with them in Gaza, their colleagues died or fled, and Israeli military authorities adamantly deny targeting journalists or provide only scant information when they acknowledge press killings. Critical information about their lives and work may have been lost forever. (See more about our methodology for documenting journalist deaths here and here.)

The 2023 global total – the highest since 2015 and an almost 44% increase on 2022’s figures – includes a record number of journalist killings – 78 – that CPJ research determined were work-related, with eight more still under investigation. Thirteen media workers also were killed last year.

More in this report:

How CPJ’s methodology has been used in the Israel-Gaza war

Interactive map: Attacks on the Press in 2023

Once the deaths in Gaza, Israel, and Lebanon are excluded, killings dropped markedly compared to 2022, when CPJ documented a total of 69 deaths, 43 of which were work-related. Outside of the deaths in the Israel-Gaza war, 22 journalists and media workers were killed worldwide in 2023. CPJ’s research confirmed that 13 of those deaths were work-related; the circumstances around the remaining deaths are still being investigated. In the 18 other nations where journalists were killed in 2023, CPJ documented one to two deaths in each.

However, the declining number is not an indication that journalism has become safer in other parts of the world. Indeed, CPJ’s annual prison census found that 2023 jailings of journalists – another key indicator of conditions for journalists and press freedom – remain close to record highs established in 2022.

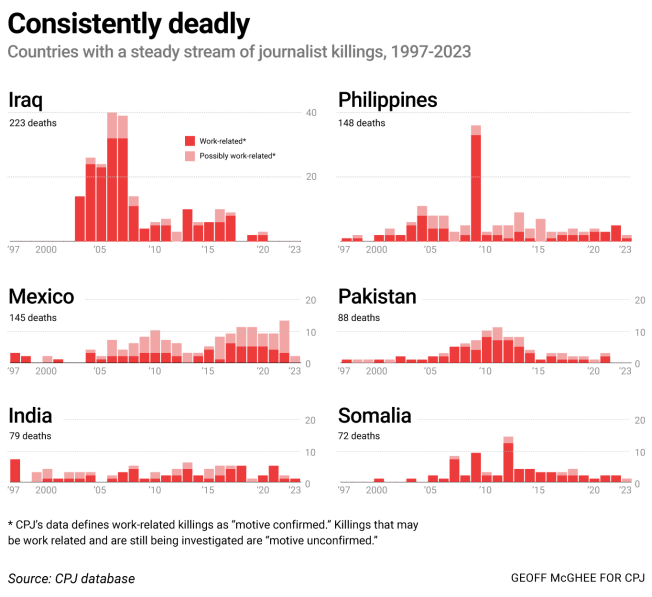

Divisive elections, rising authoritarianism, ongoing conflicts, and powerful and expanding organized crime networks create conditions that continue to put journalists in peril. In some nations, these threats have become entrenched, resulting in the killings of at least one journalist a year for decades.

Targeted killings of journalists in direct reprisal for their work, which CPJ classifies as murder, also persisted in 2023, with CPJ recording journalist murders in nine countries around the world.

In Mexico, where corruption and organized crime have long made it especially hard to determine whether a journalist’s killing was work-related, the country’s overall number of deaths fell from a record of 13 in 2022 to two in 2023. Nonetheless, journalists continued to face attacks, harassment, threats, and abduction, with a soon-to-be-published joint report by Amnesty International Mexico and CPJ finding that Mexico “has remained one of the world’s deadliest countries for journalists.”

Ukraine’s wartime decrease in journalist killings, from 13 work-related deaths in 2022 to two in 2023, may be due to factors such as improved training and safety awareness, Ukrainian authorities’ introduction of stricter accreditation rules for frontline work, and the stabilization of combat zones. Nevertheless journalists in Ukraine remain at great risk and early 2024 has already seen missile strikes that have injured journalists and attacks that may be targeted.

And while killings in regions outside the Middle East have mostly dropped, the death rate in sub-Saharan Africa has held steady, with six journalists killed per year since 2021. These totals include both deaths deemed to be work-related and killings still under investigation.

How CPJ’s methodology has been used in the Israel-Gaza war

Classification changes

CPJ researchers take extensive steps to confirm information from a minimum of two sources about every casualty listed in our database. Their first step is to determine that the victim met our definition of a journalist – someone who covered news or commented on public affairs through any medium – by reviewing examples of their previous work. Our next step is to investigate whether the journalist’s death was work-related, by speaking to as many colleagues, family members, supervisors, and friends as possible to verify the backgrounds and affiliations of those killed and the likely motives for their deaths. Determining these circumstances can take months or years – especially in war zones – and we routinely update our database if we obtain new information. Since we began recording journalist casualties at the start of the Israel-Gaza war, we’ve made the following changes to the initial entries in our database:

- Journalists removed from casualties list

CPJ has removed two Palestinians from its list of work-related casualties: one who was reported as dead but later was found alive, and another whose family later clarified that he was not a journalist or media support worker. We also removed the names of two Israeli journalists who were among the scores killed when Hamas attacked a music festival in Israel on October 7 after their outlets told CPJ they were not assigned to report on the festival. (CPJ’s global database of killed journalists includes only those who have been killed in connection with their work or where there is still some doubt that their death was work-related.)

- Targeted murders

As CPJ and other organizations investigate the cause of death for journalists, they may determine that those journalists were deliberately targeted for their work. CPJ classified as murder the 2023 killing of Reuters videographer Issam Abdallah and is investigating evidence indicating that the IDF targeted around a dozen others.

Key takeaways from CPJ’s research on journalist killings in 2023

Targeting of journalists is a growing concern

Targeted killings of journalists in direct reprisal for their work, which CPJ classifies as murder, persisted in 2023, with cases recorded in nine countries.

Almost all of the journalists killed in the Israel-Gaza war were Palestinian, and CPJ has raised concerns about the deliberate targeting of members of the media by the Israeli military.

Cases include that of Issam Abdallah, a Lebanese visual journalist for Reuters. Independent investigations by international news organizations and rights groups found evidence indicating that Israeli forces targeted a group of reporters – killing Abdallah and injuring six others – in southern Lebanon on October 13. The journalists, all wearing press insignia, were covering border crossfire between the Israel Defense Forces and pro-Hamas militants from Lebanon’s Hezbollah group in the days after Israel responded to Hamas’ deadly October 7 incursion by launching devastating retaliatory strikes on Gaza. The investigations found that Abdallah’s group was reporting from a location where no fighting was taking place when they were hit by two Israeli shells.

In January 2024, journalists Hamza Al Dahdouh and Mustafa Thuraya were killed in what Israel acknowledged was a targeted attack on a car in which they were traveling. It accused Al Dahdouh, who worked for Al-Jazeera, and freelancer Thuraya of being members of terrorist groups – a charge strongly denied by Al-Jazeera and the men’s family and colleagues. In CPJ’s May 2023 report “Deadly Pattern,” CPJ noted several cases in which journalists killed by Israeli forces were accused of being terrorists and in which no credible evidence was ever produced.

CPJ, along with other organizations, is now investigating whether a dozen other journalists – and, in some cases, members of their families – killed in the Israel-Gaza war also were targeted by the Israeli military. These cases include Al-Jazeera cameraperson Samer Abu Daqqa, who bled to death after Israeli authorities blocked efforts to evacuate him. The probes into these killings are taking place against the backdrop of the “Deadly Pattern” report, which found that members of the Israel Defense Forces had killed at least 20 journalists over the past 22 years and that no one had ever been charged or held accountable for their deaths.

Elsewhere, targeting of journalists remains a constant in countries like the Philippines, Mexico, and Somalia, which have had a historically high rate of journalist murders. From 1992 to 2023, 94 of the 96 journalists killed for their work in the Philippines were murdered; 61 of 64 work-related killings in Mexico were murders, as were 48 of 73 in Somalia. Notably, overall deaths of journalists in these countries occurred at a consistent rate: at least one journalist per year was killed for close to two decades or more.

In the Philippines, radio journalists in particular are vulnerable as radio remains an influential platform. Cresenciano “Cris” Bundoquin, a radio journalist covering local politics, was shot at least five times by two assailants on a motorcycle as he was opening a store he owned.

In Somalia, the number of killed journalists is lower than the peaks CPJ recorded between 2009 and 2013, but impunity remains high and government efforts to bring the murderers of journalists to justice do not seem to extend beyond rhetoric. Elsewhere in Africa, deaths in Cameroon saw an uptick in 2023, with at least two journalists, Martinez Zogo and Jean-Jacques Ola Bebe, murdered in the midst of a succession battle for power and state resources between factions of ailing President Paul Biya’s government.

An ominous statistic underpins journalist killings in Mexico, which has consistently ranked as one of the world’s deadliest countries for reporters. While only two killings with unconfirmed motives were documented in 2023, the nation has the most missing journalists in the world, with 16 still unaccounted for – many after a decade or more.

Justice is unlikely for the journalist victims of targeted murders. CPJ’s 2023 Impunity Index report found that of the nearly 1,000 murders CPJ has recorded since it began collecting data in 1992, a total of 757 – more than 79% – have gone wholly unprosecuted.

Documenting 2023 deaths was especially challenging

CPJ independently investigates every journalist death to determine whether they were killed in relation to their work. In the usual course of an investigation, researchers interview family, friends, colleagues, and authorities to learn as much as possible about a journalist’s work and the circumstances of each killing. As noted above, this was particularly challenging given the high number of killings in such a short period in Gaza and the lack of independent access to the territory.

Beyond the Israel-Gaza war, other forces hampered CPJ’s efforts to tell the whole story around journalists’ deaths in 2023. Among the eight who CPJ could not confirm were killed in connection with their work, lack of information from police and government officials, sometimes fueled by pressure from corrupt and criminal actors, keeps these deaths shrouded in mystery. These deaths include:

- Nelson Matus Peña, who survived a prior assassination attempt and was shot to death in a parking lot in Acapulco, Mexico.

- Juan Jumalon, who was killed during a live broadcast at his home-based radio station in the Philippines.

- Abdifatah Moalim Nur (Quys), killed in a suicide bomb attack at a restaurant in the Somali capital, Mogadishu.

Even if a journalist is deemed to have been killed for their work, details about their cases may be difficult to obtain. Because almost all of those categorized as having been killed in relation to their work – 77 out of 78 in 2023 – were local journalists, often covering crime, conflict, and corruption in their communities, their deaths rarely attract international attention, and pressure on their families and colleagues to stay silent can stymie the quest for justice. Because the powerful – whether in government or in criminal organizations – often seek to bury these investigations, the cases of many journalists killed years ago remain unsolved.

No safety in lower numbers

CPJ research has shown dangers remain for journalists, even in countries where the number of killings declined in 2023.

Mexico provides an important case in point as to why journalist killings can drop, but conditions can remain just as dangerous. Although the number of killings in Mexico dipped significantly, from 13 in 2022 to two in 2023 (including both work-related deaths and those where the motive was still being investigated), there were no new government policies or societal shifts to explain a decline that may have been a statistical outlier. (While several other journalists were killed in Mexico in 2023, CPJ did not include them in its database after finding their deaths were unrelated to their profession.)

What is clear about Mexico is that there were a large number of non-lethal attacks in 2023, in line with numbers in previous years, and the intention in some cases may have been to kill. Journalists continued to face harassment and threats from organized crime members and public officials, with systemic impunity facilitating these attacks. Mexican government agencies spy on reporters and rights defenders and a significant number of journalists have had to leave their homes, and abandon their professions, due to violence.

Haiti also saw journalist killings decrease in 2023, but the country remains plagued by violence and instability, with an increase in physical attacks by police and gangs in the last two years, and with crimes committed against journalists highly likely to go unpunished.

The threats to journalists can be expected to continue in 2024 as conflicts persist, impunity remains systemic, and a record number of high-stakes elections are held around the world.

Methodology

CPJ’s database of killed journalists is divided into two main categories: “confirmed” and “unconfirmed.” Deaths are classified as “confirmed” when the evidence indicates a journalist was killed in connection with their work, unconfirmed when there is insufficient information to determine the motive for the killing.

Since Russia’s full-scale assault on Ukraine in February 2022, CPJ has documented all war-zone journalists – whose deaths and journalistic credentials we are able to verify – as “confirmed” to be working whether they were at home or in the field – an assumption based on the fact that technological advances allow them to work from anywhere – unless it can be definitively proven otherwise.

Confirmed deaths fall into three sub-categories: targeted murders in reprisal for reporting work, deaths in combat zones or crossfire, and deaths on dangerous assignments. CPJ also records the killings of media support workers, such as translators, drivers, and security guards.

CPJ continues to investigate unconfirmed killings where possible and changes classifications when new information becomes available. (Read more about how we gather and classify our data)

CPJ’s research and documentation covers all journalists, defined as individuals involved in news-gathering activity. This definition covers those working for a broad range of publicly and privately funded news outlets, as well as freelancers. In the cases CPJ has documented, multiple sources have found no evidence to date that any journalist was engaged in militant activity.

Kathy Jones is the deputy editorial director at the Committee to Protect Journalists. For more than two decades, she has helped shape and tell stories with data, reporting and visuals for news organizations including Reuters, Bloomberg, and Newsweek.